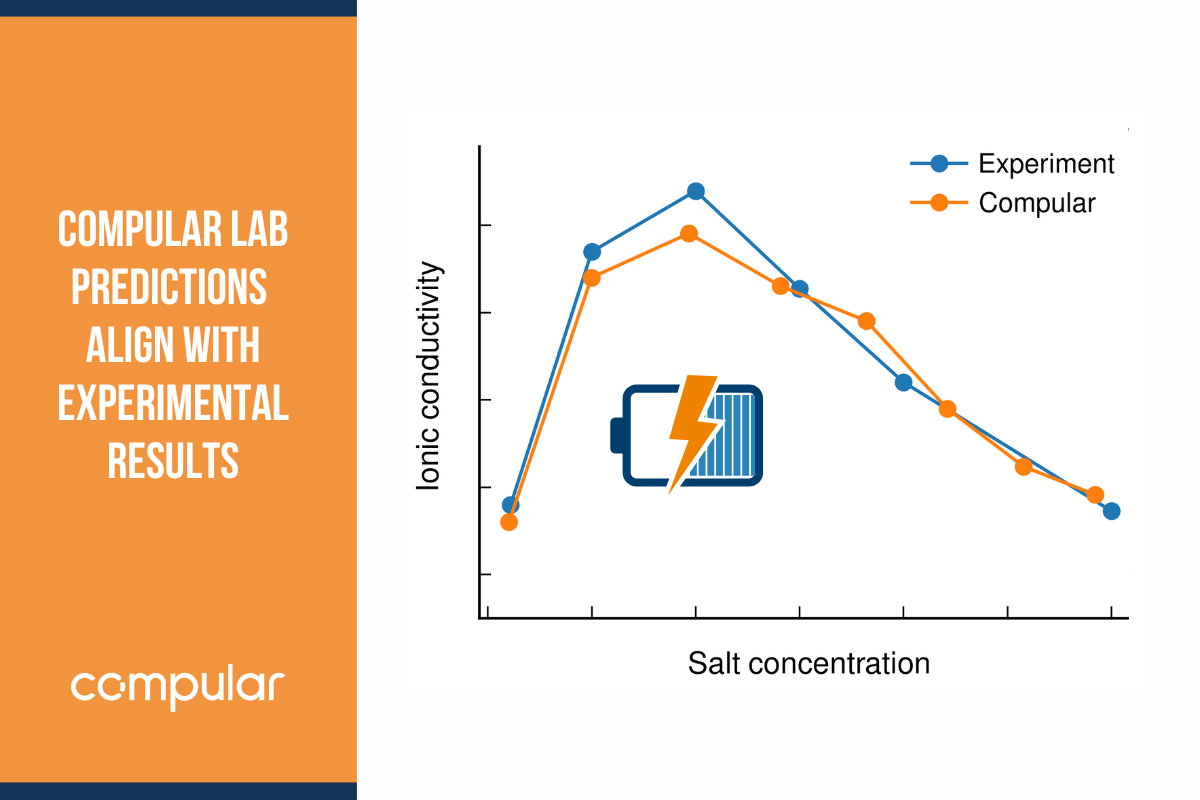

As a CTO in materials informatics, I have kept track of recent AI developments, even though our own solutions are more based on physics and good old-fashioned statistics than the large language models (LLMs) and multimodal models that have made so many recent headlines. A year ago, my attention on AI developments was mostly driven by academic curiosity. Since then, and especially since the launch of ChatGPT, it has become obvious that AI will change how work is done in every sector, and in every company, in the near future. ChatGPT had so fast user uptake that it left everything that came before it in the dust. Instagram, the former record holder, took 2.5 months to reach one million users. For ChatGPT it took only 5 days. That’s a factor of 15, which is simply off the charts. Previous overtakings have been 2x at best.

AI productivity tools have naturally found their way into how we work at Compular. A few examples are the Github Co-Pilot for AI-driven code completion, next word suggestions in Google Docs, and certainly not least, ChatGPT, which I think most of us use almost daily, thanks to its limitless uses. I personally use it for so many disparate things that I couldn’t list them. Where I used to search Google Scholar for systematic reviews, I may today just ask ChatGPT to summarize the main findings of a field. If I have follow-up questions, it is so much easier to ask ChatGPT than to search in the document for an answer that might not even be there. And if I wonder why helium is so scarce on Earth, while being so abundant in the Universe, ChatGPT is a quicker and more precise route to the answer than Google.

At one point I needed to brush up my knowledge on how to compute chemical reaction pathways and transition states. ChatGPT quickly gave me a list of relevant methods and a basic description of each that allowed me to filter among them. After some follow-up questions I was able to much more efficiently find and acquire the deeper knowledge I needed from the academic literature.This saved me hours of less directed search.

At another occasion, I had a clear idea of a statistical physics derivation I would like to do, but it was a bit messier than I had the appetite for at the moment. So I explained it to ChatGPT in enough detail to enable it to complete the task. Its answer, which came within seconds, was flawless both in the derivation itself, and in its explanation of the steps taken. This probably saved me at least a half-hour of tedious algebra.

As far as I can tell, GPT-4, while perhaps not quite generally intelligent, clearly exhibits a form of general intelligence. The importance of AI breakthroughs tend to be downplayed after the fact, with the effect of moving the goalposts for “real” AGI. But I would argue that the list of tasks AIs are not yet capable of performing is shrinking at a noticeable rate, even as people try their best to come up with new ones.

To begin with, state-of-the-art LLMs really can hold intelligent conversations in very nearly any topic. I think of GPT-3.5 as a very knowledgeable high-school graduate who had straight A:s in all topics. GPT-4 feels more like a college graduate in its depth and nuance of reasoning in technical fields, though it still makes trivial mistakes from time to time. It has been found that recent LLMs exhibit clear signs of theory of mind, they seem to perform like a typical STEM college graduate in IQ tests for humans and apparently they are above average among accepted candidates for several demanding professional entry exams. It was also found to be an avid user of software tools if given the opportunity.

For all its prowess, there are still tasks GPT-4 cannot do. One is that because it is a single-pass feedforward neural network it cannot directly reflect on its earlier output. It also lacks agency since it simply reacts to prompts and doesn’t plan its next actions. Another limitation is that it is static once pre-trained, i.e. it lacks the ability to learn continuously from new experiences. And it is still awfully prone to hallucination and rather lackluster at doing algebra and other computational tasks.

However, many of these holes in its competence are rather easily plugged, and this is already being done. For instance, while it doesn’t reflect on its answer while writing it, it already has the attention span to let users ask it to critically reflect on previous answers and update them accordingly. It is not hard to imagine someone building algorithms in which final answers are based on some form of iterative improvements to previous attempts. In addition, the recent announcement from OpenAI on adding plug-ins to ChatGPT, as well as the embedding of GPT-4 and similar AI systems into miscellaneous software, will wildly enhance their capabilities (remember, GPT-4 is a competent tool user). It is also not all too hard to imagine in the near future, given the already huge successes in multimodality, that someone would give GPT-4 or something else a robotic body (or a couple thousand) and some more long-term, less narrow goals, and that this would result in something very reminiscent of human or animal agency.

So what does all this mean from a practical standpoint? Well, this is huge. In terms of productivity gains this is at the very least on par with, and likely far exceeding, the personal computer and Internet revolutions. Any creative or knowledge-based task you perform on a computer can now be done much faster, and often with greater final results by leveraging the power of AI.

This kind of overturn of how things are done throughout the economy always has strong higher-order effects that are very hard to predict, and take years to play out. To name some historical examples: cars gave birth to suburbs, the Internet closed bank offices, and social media disrupted everyone’s attention spans. It is too early to predict what higher order effects AI will have when used at scale. Some jobs will surely vanish, others will simply become much more productive. Some problems will be solved much earlier than otherwise, while new ones will emerge. Just like user-generated content went from negligible to the majority of Internet content, so will AI-generated content. This means much more high-quality content, but also much more plausible-looking misinformation and the increasing uncertainty of whether you are interacting with a human or a machine online.

And if the current rate of progress continues apace, or keeps accelerating, how far away are we really from true superintelligent AGI? Once that happens, all bets are off. This does indeed seem like a good time to start seriously taking steps towards mitigating that risk, as called for in a recent open letter from the Future of Life Institute. Just the solutions that can already be built on top of existing models such as GPT-4 without further training are mind-boggling and far from fully realized yet, so I think the world could deal with not getting even stronger models trained for half a year. Spending more effort on understanding the inner workings of these models definitely seems like a good idea. Both a voluntary pause and an enforced moratorium also seem to be quite doable at present, since almost all leaders in the field are gathered in (or at least owned by) Silicon Valley. But on the other hand, there is also merit to the argument put forward by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and Yann LeCun, chief AI scientist at Meta, that the only way to safely launch new technologies is to roll them out slowly, test them empirically and iterate. But then again, the quantum leaps seen so far between generations of GPT makes it alarmingly plausible that a future version would be intelligent enough to fool us and unaligned enough to want to.

Whatever happens next, one thing is clear – there will be interesting times ahead!

Rasmus Andersson, PhD

CTO Compular